Thailand’s revered monarch, the world’s longest-serving head of state, lived to serve his people as the “strength of the land”, as his parents named him.

BANGKOK: King Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand, the world’s longest-reigning monarch, died on Thursday (Oct 13) at the age of 88. The world’s longest-reigning monarch, Thailand’s King Bhumibol Adulyadej, died in hospital on Thursday (Oct 13), the palace said in an announcement. He was 88. “His Majesty has passed away at Siriraj Hospital peacefully,” the palace said, adding he died at 3.52pm Bangkok time (4.52pm Singapore time). Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha, in a televised address on Thursday evening, declared that mourning will last for one year, and flags will fly at half mast for 30 days. There will be no entertainment for 30 days too.

The only king most Thais today have ever known, he reigned over the country for 70 years, after succeeding his elder brother King Ananda Mahidol on Jun 9, 1946.

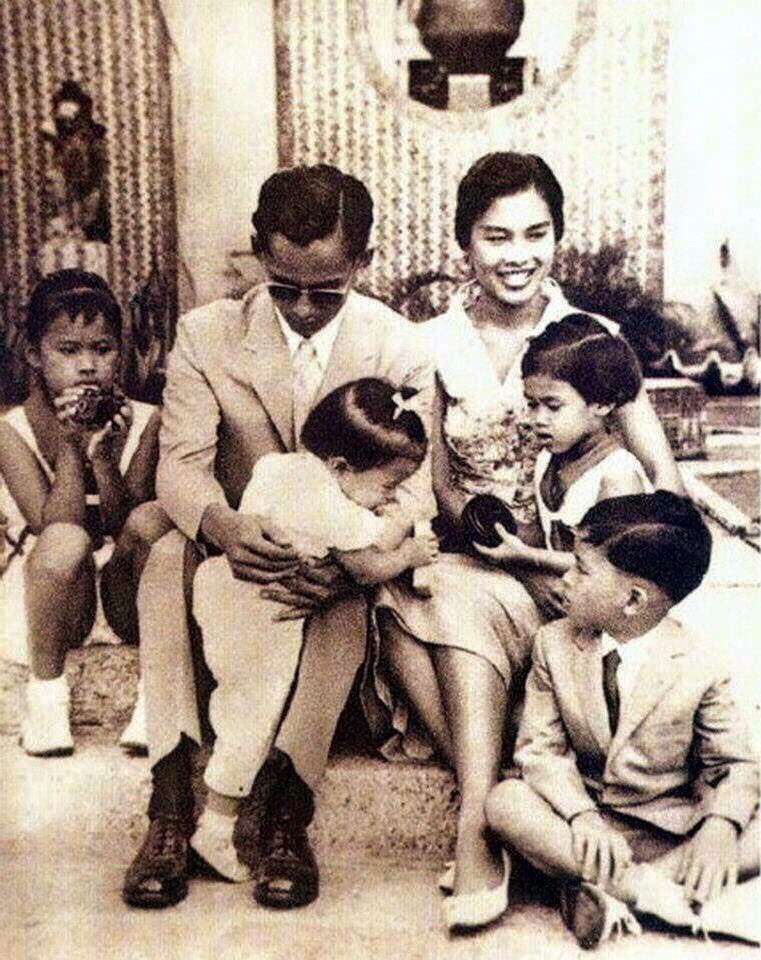

Survived by his wife Queen Sirikit, 84, the popular monarch leaves behind a son, Crown Prince Maha Vajiralongkorn, and three daughters, Princess Ubol Ratana, Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn and Princess Chulabhorn Walailak.

At the age of 18, Bhumibol became the ninth monarch of the Chakri dynasty, or King Rama IX.

His reign came at a critical time when Thailand was evolving as a constitutional monarchy. Emerging as the single unifying force of the nation, King Bhumibol brought about a revival of the institution which had been on a path to obsolescence.

According to the Constitution, the monarch was the head of state and commander of the Thai armed forces, but held little formal political power.

In reality, however, King Bhumibol was one of the most powerful figures in Thailand, as well as its main pillar of stability – which he demonstrated by returning calm to the country with just a few words during bloody political crises in 1973 and 1992.

Not only did his words wield profound influence, his actions also inspired deep respect while his ideas indelibly shaped the course of Thailand’s development and its people’s lives.

Throughout his reign, he was beloved and highly revered by Thais, many of whom regarded him as a semi-divine father figure.

His portrait was everywhere, hung on walls or placed on altar tables inside government buildings, banks, schools, shops and homes. People knelt and bowed when he appeared; many would weep with joy.

Their deep reverence and admiration – which still often puzzles many in the outside world – grew with what was seen as his selfless devotion to the well-being of his people, from the moment he placed upon his head the Great Crown of Victory during his coronation.

THE KING FROM AMERICA

King Bhumibol’s life story is a remarkable one. He was an American-born son of Prince Mahidol Adulyadej of Songkhla – the half-brother of King Prajadhipok, or Rama VII – and his commoner wife, Sangwal.

On Dec 5, 1927, when he was born at Mount Auburn Hospital in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Bhumibol was not meant to become king. The monarchy in Thailand, then known as Siam, was withering.

But an incident in 1932 changed his destiny completely.

A bloodless revolution transformed Thailand from an absolute monarchy into a constitutional one. The growing power of the military soon led to the abdication of King Rama VII, and the crown was passed to Bhumibol’s nine-year-old elder brother Ananda.

By that time, his father had already passed away and the family had relocated to Lausanne in Switzerland, a world away from political instability back home. Bhumibol spent most of his youth with his mother, brother and sister Galyani Vadhana on the peaceful shore of Lake Geneva.

He studied French, German and Latin, and entered the prestigious Lausanne University to pursue a degree in science.

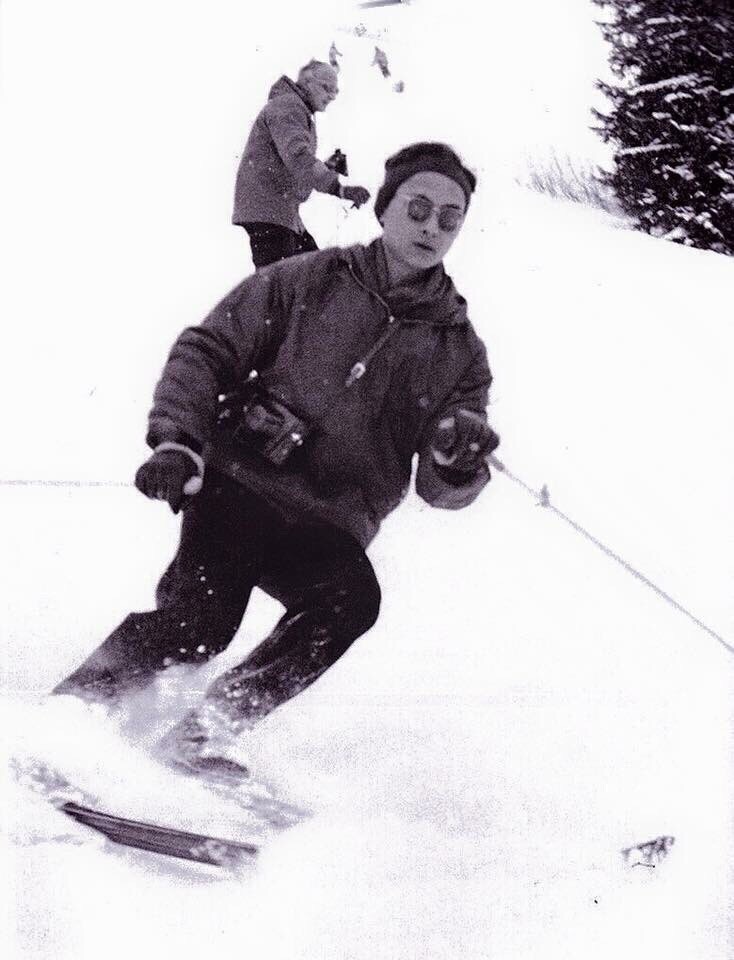

He developed a passion for skiing, sailing and jazz music – he played saxophone, clarinet, piano and trumpet. His musical talent later led him to rub shoulders with jazz giants such as Benny Goodman, Lionel Hampton and Benny Carter in jam sessions.

Following the end of World War II, the Mahidol family paid a temporary visit to Thailand. Shortly before the princes’ departure for Lausanne to finish their studies, King Ananda died from a gunshot wound.

His sudden demise made Bhumibol the rightful heir to the Thai throne in 1946. But the latter was not yet ready.

The young king returned to complete his studies in Switzerland, switching his major to law and political science as he prepared for his future as king.

While back in Europe, he lost the sight of his right eye in a motoring accident; but won a bride in the form of Sirikit Kitiyakara, daughter of the Thai ambassador to France.

But before his departure for Europe, an incident gripped his mind.

He wrote in his diary: “On the Ratchadamnoen Klang Road, people came close to the car in which I was sitting. I was so afraid it would run over their legs. The car went past the crowds at the slowest speed possible before going slightly faster when we reached the Benchamabophit Temple.

“Somewhere along the way, I heard someone shout: ‘Don’t abandon the people’. I wish I could have shouted back: ‘If the people don’t abandon me, how could I abandon them?’, but the car, which was going fast, had already left that person far behind.”

The story was published the following year in the Wong Wannakhadi journal. It has since been imprinted on the minds of many Thais, who regard King Bhumibol not only as their monarch but also a father who devoted his life to the well-being of his people, his children.

THE KING’S PROMISE

For most of his youth, King Bhumibol had lived abroad. Thailand was almost alien to him.

But work as a king closed the gap between the young monarch and his people, as he described in a letter to a friend in Switzerland.

“When I was studying in Europe, I never realised what ‘my country’ was, or how it was related to me,” he wrote. “Not until I knew my people when I communicated with them did I realise that precious love.

“I was not really homesick, but I learnt through working here that my place in this world is among my people, that is, all the Thai people.”

It was only on May 5, 1950, some four years after his brother’s death, that Bhumibol was officially crowned.

At his coronation at the Royal Palace in Bangkok, the King promised his subjects: “We will reign with righteousness for the benefit and happiness of the Siamese people.” Over the 66 years that followed, he kept his promise.

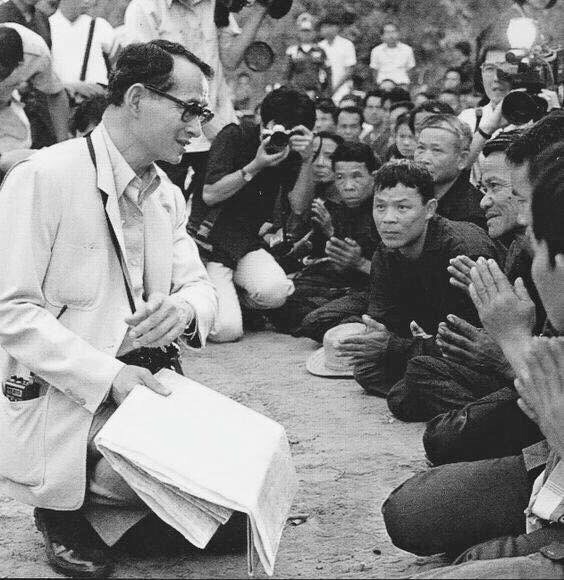

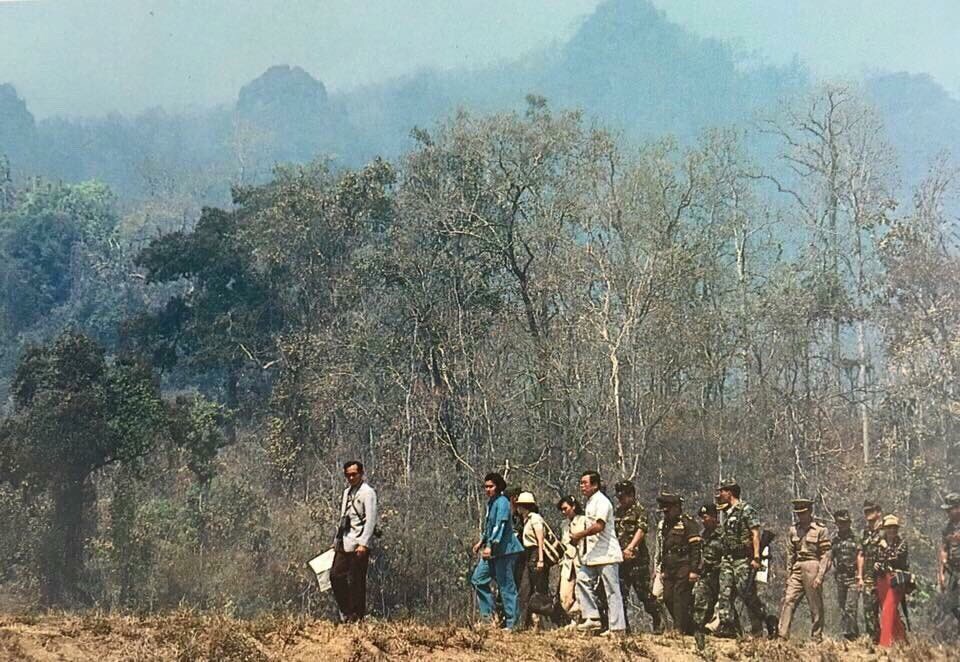

He travelled across the country to meet his people: Central Region, Northeast, North, South, East and West – he covered them all. Petitions were submitted and received.

Tirelessly, he worked to improve lives, particularly of the poor, and to promote development in the rural areas. He was often seen travelling on foot over rough terrain, visiting remote communities with a camera slung around his neck and a huge map he had compiled in his hands.

The King was close to his people. He talked and listened to them during each visit, learning about their lives and problems. Each time, he made notes.

With this first-hand information, he searched for solutions. The result has been more than 4,000 development projects nationwide, ranging from irrigation, farming, conservation, flood and drought mitigation, to drug control, public health and distance learning.

His crop substitution project was integral to the decline of opium production along the borders with Myanmar and Laos. His pioneering efforts in artificial rain-making resulted in Royal Rainmaking Technology, which changed the lives of countless farmers in drought-stricken areas.

The highly successful patented technique was even adopted by the Australian state of Queensland to combat its own drought problem.

THE PHILOSOPHER KING

His philosophy of sufficiency economy also won praise internationally. It is a method of development that shifts the emphasis from industrial expansion to stable basic economy. Moderation, prudence and risk management are at its core.

But it was not until 1997 that the philosophy was widely embraced.

At the time with its economy excessively driven by exports and foreign capital inflows, Thailand was hit by a financial crisis that quickly spread through East Asia. The baht was devalued. Companies went bankrupt. Unemployment rose. It was then that the King addressed the nation.

“People were crazy about becoming a tiger. Being a tiger is not important,” he said in a speech marking his 70th birthday.

“The important thing is for us to have a sufficient economy. A self-sufficient economy means to have enough to support ourselves.

“It does not have to be 100 per cent or even 50 per cent, but perhaps only 25 per cent will be bearable. A careful step backwards must be taken; a return to less sophisticated methods must be made with less advanced instruments. It’s a step backwards in order to make further progress,” he added.

In 2006, King Bhumibol became the first person in the world to receive the United Nations’ Human Development Lifetime Achievement Award.

It praised his philosophy and recognised his “extraordinary contribution to human development” through various projects which, as the UN described, helped “millions of people in rural areas regardless of their citizen status, ethnicity or religion”.

The King was also bestowed awards by other organisations worldwide, including the Philae Medal from UNESCO for his devotion to rural development and people’s well-being; a World Health Organization plaque in recognition of his moral leadership and example in public health; and the first Dr Norman E Borlaug Medallion from the World Food Prize Foundation for his outstanding humanitarian service in alleviating starvation and poverty.

“THE KING CAN DO WRONG”

Throughout his reign, King Bhumibol was protected by a strict law known as lese majeste, which penalises whoever defames, insults or threatens the King, the Queen, the heir-apparent or the Regent. Section 112 of Thailand’s penal code states that those guilty of lese majeste can face up to 15 years in jail.

The Thai constitution also makes it clear that “the King shall be enthroned in a position of revered worship and shall not be violated” and that “no person shall expose the King to any sort of accusation or action”.

As the number of people prosecuted under the loosely worded law rose following the military coup in 2014, it came to be seen by some as a weapon used by the political authorities to silence criticism against the government.

King Bhumibol himself publicly refuted the traditional practice that constitutionally bars violation against the monarchy and the engrained idea that “the King can do no wrong”.

In 2005, in his address to well-wishers on the occasion of his 78th birthday, he said: “Actually, the belief that ‘the King can do no wrong’ is a big insult to the King. Why could he do no wrong? By saying so, you mean the King is not a human being. The King can do wrong. If, by criticising the King means violating him, then I don’t mind the violation.”

He noted: “I myself have never imprisoned anyone for rebelling against me. If they’re sent to prison, I pardon them. I won’t sue them because it’s the King who will end up in trouble.”

Nevertheless, the lese majeste law remains fully effective in Thailand. Thai Prime Minister General Prayut Chan-ocha, who led a coup that ousted Yingluck Shinawatra’s elected government in 2014, maintained that the country needed it to protect the monarchy because “the institution is not in a position to sue anyone”.

THE PEACE-BRINGER

Taking place during King Bhumibol’s reign were a number of military coups, changes of government and constitutions, and street protests that ended in bloodshed.

In such key moments, an audience with key actors behind closed doors could tip the balance, as could his withholding of a royal endorsement of a coup; while his public appearance breathed calm into the nation in turmoil. His words restored peace.

On Oct 14, 1973, demonstrators led by university students faced a violent crackdown by armed forces. The order was given by the ruling military government under Field Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn.

That evening, King Bhumibol addressed his people. His speech, broadcast on radio and television, was simple. It was powerful.

Calling it “the day of great sorrow in the history of the Thai nation”, the King asked all sides to end the violence and apply restraint. His words defused the bloody confrontation. Calm returned to the streets of Bangkok.

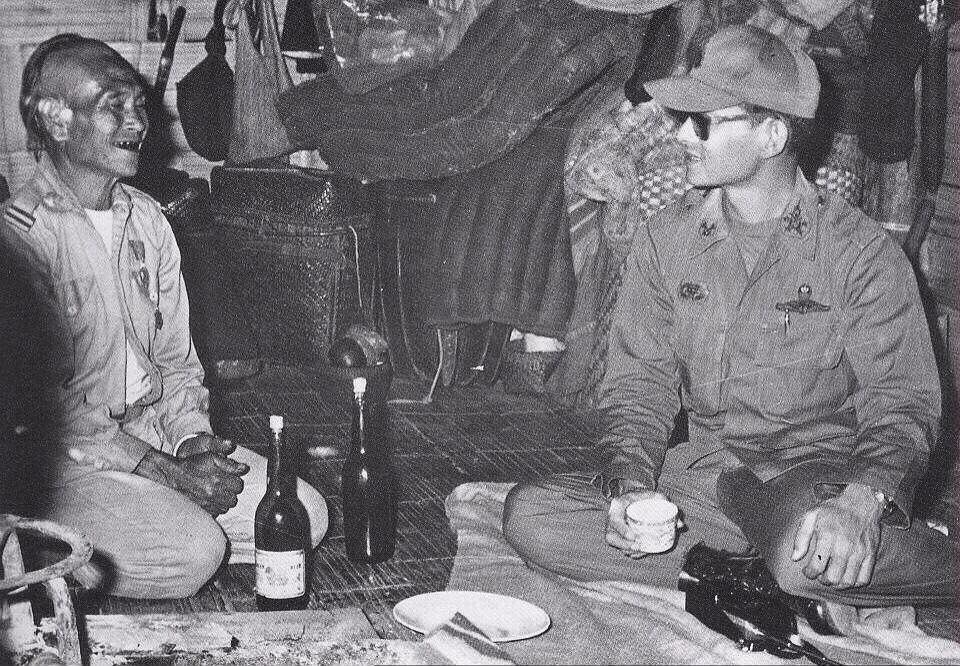

Almost two decades later, in 1992, the whole country once again witnessed how the King returned peace to the kingdom in a nationwide televised broadcast.

Thailand was going through a difficult time. Weeks of massive demonstrations led by politician Chamlong Srimuang against the self-appointed Prime Minister, General Suchinda Kraprayoon, had triggered a bloody clampdown by armed forces. More than 50 people had been killed, many had disappeared; hundreds had been injured.

Two days later, the two protagonists appeared kneeling in front of King Bhumibol. The whole nation watched. Said the King: “If you continue to confront each other, Thailand, which has taken so long to come this far, will be ruined. I asked both of you to come here not to confront but to unite.

“Each of you represents different parties that should not fight each other but jointly solve the problem, the violence that has occurred. Once it’s reconciled, you two can discuss how the country can move forward,” he told them.

King Bhumibol had little formal political power. He held no arms. But his words and presence drew obedience. Within hours, the rally was dispersed and protesters were granted amnesty. General Suchinda resigned. Both he and Chamlong left politics and peace returned to the country, which held a general election four months later.

BHUMIBOL: STRENGTH OF THE LAND

Many Thais still remember these two historic moments when a country in turmoil was rescued by their king, Bhumibol Adulyadej – which in Sanskrit, translates as “strength of the land, incomparable power”.

The name Bhumibol was once explained by the King himself: “Mother said: ‘Actually, your name is Bhumibol, which means strength of the land. I want you to remain with the land’.

“After hearing that, I thought about it. I believe my mother was trying to teach me and tell me that I should be down to earth and work for the people.”

For Thais, that is exactly what he did.

Throughout his life, the King worked for the peace, prosperity and stability of the nation. He once said it would all come true “if everyone in the nation discharges his duty with all his might and puts the common interest before his own”.

His actions set just such an example.

– CNA/pp… Photos Thai Public Relations Department

Condolences to Thailand and all Thais from Misterology.